On social media, a major terrorist attack like last night’s in Manchester can trigger a bewildering hubbub of delusions, hoaxes, noise, and some early glimmers of truth. Here’s how to start filtering:

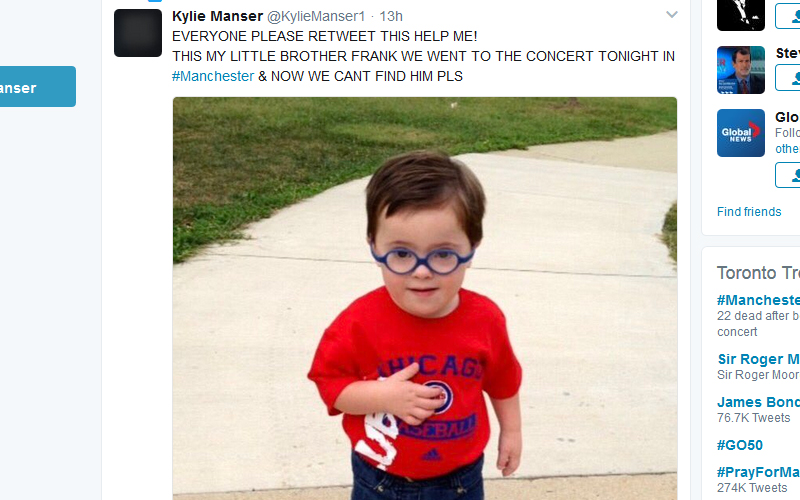

1. Have nothing to do with please-find-my-relative social media posts

Are they all fake? It’s hard to know, but certainly many of them are.

It’s not hard to imagine the anguish of someone who can’t contact a family member after a terrorist attack, and it’s not hard to imagine them taking to social media as a result. And it’s not hard to imagine strangers, trying to be helpful, retweeting and sharing until there are tens of thousands of retweets and shares. (They seem not to have thought through how this would constructively respond to the problem, but let’s assume that the intentions behind it are good.)

Consistently, though, a lot of these posts are fake.

This is something that consistently happens after terrorist attacks. The motivations behind it are murky and seem to vary.

One of the strangest examples was the online claim that Mexican journalist Tamara De Anda was missing after the Westminster Bridge attack in London in March. De Anda, who was in Mexico at the time of the attacks, had recently published a story about someone being fined after harassing her on the street. Online trolls targeted her after that, and when the London attacks came along it became the pretext for a viral hoax targeting her.

Last night’s attack was no different. Buzzfeed has a roundup of fake victims. An Australian photographer, for example, found her 12-year-old daughter’s photo on social media, circulated as missing in Manchester (she’s fine, and in Australia).

A more elaborate hoax targeted an American Youtube personality who, as he points out, is just fine and not in England at all, despite what a viral tweet claimed:

Typically tweets like this make an emotive claim based on a relationship: a sister, brother, child. What they’re short on, usually, is what form help could usefully take — are people expected to wander the streets of Manchester, phones in hand, peering at strangers’ faces and preparing to ask “Are you @GamerGateAntifa’s un-named son?”

The fact that real distraught parents really can’t find their real children makes hoaxes of this kind more grotesque:

From a distance, though, there’s no good solution other than not recirculating posts of this kind.

READ: ‘Pls help me’: Manchester explosion has parents frantically seeking missing kids

READ: Manchester attack: Mother makes desperate appeal for information on her missing daughter

2. Don’t trust the tabs

In an ideal world, tabloids would report the news in a brisk, short format, but with the same discipline as other news outlets. In practice, the temptation to feed the beast with something shiny from social media can prove too strong.

In this case, a panicky Facebook post from one individual incorrectly claiming a gunman had been seen at an area hospital led directly to reports in the Daily Star and the Daily Express presenting it as fact. (Both stories have changed, but Buzzfeed has the screenshots.)

(In a complicated emergency, it’s not hard to imagine reports that one local hospital was unusable having serious consequences.)

A collage of what were presented as pictures of missing concertgoers (which included two people who are just fine and on other continents, a different journalist in Mexico and a 2013 murder victim) hasn’t worn well, despite an appearance on Fox (compare the image at the 30-second mark to the man above):

The Daily Mail also tweeted the image, although it has since disappeared. Where it originally came from isn’t at all clear.

A composite image of this kind, made responsibly, would involve a lot of knocking on doors, really difficult conversations, and respectful, alert attention to detail at every point. Common sense says that a version that’s published a few hours after an incident isn’t likely to have been done properly.

In 2011, Arizona congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords was shot and wounded; early reports, which said that she had died, turned out to be wrong.

“What we need to do is slow down,” journalism professor Dan Gillmor wrote at the time.

“A wonderful trend has emerged in the culinary world, called the “slow food movement”— a rebellion against fast food and all the ecological and nutritional damage it causes … we need a ‘slow news’ equivalent. Slow news is all about taking a deep breath.”

It’s a good principle to apply as a news consumer. Careful fact-gathering takes time. It’s said that a lie can be halfway around the world before the truth has time to put its boots on; as a reader, it’s wise to give the truth some time to put its boots on.

Comments