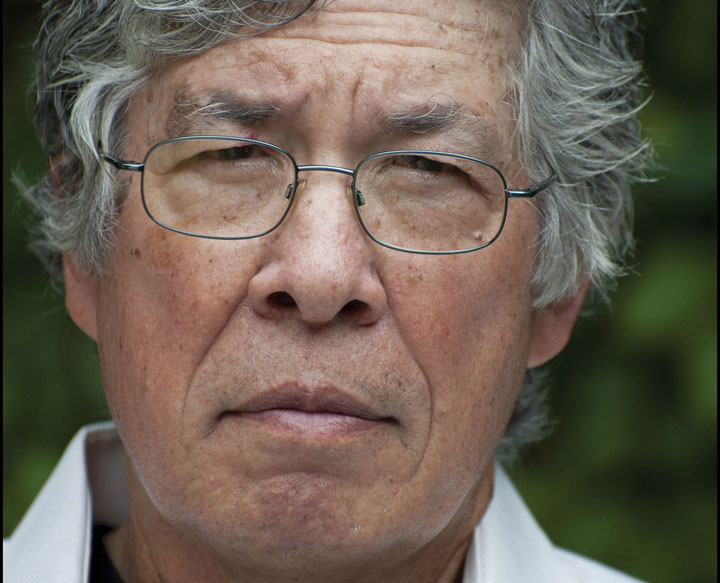

TORONTO – Writer Thomas King of Guelph, Ont., says he hopes the recent awards love for his book The Inconvenient Indian will spawn a serious conversation about the state of native peoples in Canada.

But the 70-year-old, whose deeply personal story won the $25,000 RBC Taylor Prize for non-fiction on Monday and the $40,000 British Columbia National Award for Canadian Non-Fiction last month, doesn’t think he’ll ever witness such a dialogue.

“That would be the most I could hope for, and I won’t be alive to see that, because that’s going to be a slow conversation and it’s going to take years for that conversation to bear any fruit,” King said in an interview after winning the Taylor Prize at a Toronto luncheon.

“You can’t have 400 years of government policy keeping native people down and then just simply turn around on a dime one day and undo all of that. Impossible.”

The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America beat out four other finalists for the Taylor Prize.

They included Kabul-based journalist Graeme Smith for The Dogs Are Eating Them Now: Our War in Afghanistan, which recently won the $60,000 Hilary Weston Writers’ Trust Prize for non-fiction.

Also on the Taylor Prize short list was Charlotte Gray of Ottawa for The Massey Murder, Vancouver’s J.B. MacKinnon for The Once and Future World and David Stouck of Vancouver for Arthur Erickson: An Architect’s Life.

Jury member Coral Ann Howells said the judges were unanimous in choosing King’s book, which she called “a very post-modern bricolage form of writing” blending serious historical subject matter and “idiomatic and personal kind of conversational style.”

“I think it resonates for Canadians — and indeed for those of us who live in other countries — in relation first of all to indigenous people,” she said. “But also in terms of marginalized and minority groups and the fact that what he does so amazingly is he talks about these very fraught issues, but he does it with humour and manages to make it accessible to readers’ sympathies.”

King, who was born in the U.S. and is of Greek and Cherokee descent, is also a novelist, short-story writer, screenwriter and photographer. He teaches English and Theatre Studies at the University of Guelph.

He said he added personal touches to the book so readers could know what the history of native peoples felt like.

But it was emotionally difficult revisiting parts of the past, admitted King, who was involved in native activism mostly in Utah and northern California from 1967 until about 1980. That’s when he moved to Lethbridge, Alta., to teach native history and literature at the university there and focus on becoming a writer.

“Going back through the residential school days, doing the research in there, understanding that if I had been born in that era, I probably would have been buried with many of those kids in the school graveyards — that was hard,” said King, who’s twice been nominated for Governor General’s Awards.

“It was hard to look at the land issue, which is very much an issue that is with us today, to see how much land has been taken, how much land has been destroyed — that was difficult.

“And the other part was the activist movement. I lost a lot of friends during that period of time.”

King said his activism included marches, going on TV and radio, speaking with government agencies and working with native groups on reserves. At some points they had run-ins with police and guns pointed at them.

“That was a difficult time where we were trying to do something. We weren’t sure we could do it. We were young. We were idealistic,” he said.

“And to look back at the people who did not make it through that period saddened me a great deal.”

King was so saddened during the writing process that he was ready to give it up, he said.

But his life partner, Helen Hoy, told him: “Just keep moving forward.”

“She was there to push me along a little bit and sometimes to natter at me like a little sheep dog and I got through it,” said King, who thanked Hoy in his acceptance speech and is due to publish a new novel in the fall.

“But it was difficult.”

This is the 13th cycle of the newly rebranded award, formerly known as the Charles Taylor Prize.

This year organizers are also offering a new award, for an emerging Canadian literary non-fiction writer as chosen by the winner of the main prize.

The 2014 jury also included James Polk and Andrew Westoll, whose book The Chimps of Fauna Sanctuary won the prize in 2012.

They read 124 Canadian-authored books submitted by 45 publishers.

The runners-up each get $2,000.

Comments