NAGOYA, JAPAN– There’s a sense of order in Japan. Almost without exception, people in this land of 125 million inhabitants follow the rules. Pedestrians rarely jaywalk. On busy stairwells in Tokyo Metro stations, people stand or walk on the left. In jammed subway cars, there is no jostling for position. No loud talking that would disturb others. On the streets, drivers don’t block intersections, they obey traffic laws. If someone gets cut off, they’re unlikely to engage in a verbal battle with the offender. People don’t like to attract unwanted attention.

Our group of journalists bound this morning for Nozumi Train 223 must have glaringly broken that convention about fitting in. Arriving late at Tokyo station to catch the bullet train, we all knew the famous Shinkansen would pull out promptly at its scheduled departure time of 10:20 a.m. whether we made it or not. Our horde ran with abandon up the stairs and onto the platform. We made it just in time.

Delays and deviation from the schedule are not acceptable here. A young Japanese hotel clerk, who studied high school in Nanaimo, B.C. put it this way when I expressed amazement to her about the social order: “There is value in compliance,” she said, making the point that if everybody follows the rules, well, everybody benefits.

GALLERY:Walking the floor at the 43rd annual Tokyo Motor Show

But what happens when things go wrong? Since the devastating earthquake and tsunami of March, 2011, the country has had to contend with another rebuilding project. The disaster at the Fukushima nuclear plant led the country to idle all its reactors. Despite the country’s proud engineering prowess, the country hadn’t prepared adequately for what might go wrong. Neither had Toyota, an auto company with a stellar reputation among consumers–until safety issues put the Nagoya-based manufacturer in an unfamiliar and uncomfortable spotlight.

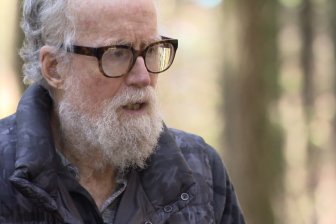

“Maybe we felt a bit too conceited,” said Mitsuhisa Kato, the 60-year-old executive vice president of Toyota Motor Corporation, answering a reporter’s question about what led to the company’s unintended acceleration crisis. Kato, an engineer who is Toyota’s head of research and development, has spent his entire career at Toyota.

“We wanted to increase profitability,” said Kato, acknowledging that with so much demand for Toyota’s products world-wide, the company may not have placed enough emphasis on safety and quality control. But that has changed, he said, and more changes are ahead.

GALLERY: Lexus unveils latest designs ahead of Tokyo Motor Show

Like many other auto makers who have been following similar systems for years, Toyota is embarking on a process of streamlining product development. Its program is called Toyota New Global Architecture or TNGA. Kato said under TNGA, about half of the components of new vehicles would be designed and manufactured for common use. The other half would be developed with local or regional needs in mind.

One motivation for the plan? Cost control. Kato says “15 to 20 per cent…can be saved using this method,” leading to efficiencies in engineering and manufacturing.

Cost, however is not the only motivation. Manufacturers say they’re focused on trying to make driving “fun” again; Toyota executives made that point over and over again during the Tokyo Motor Show.

But near the end of Kato’s half hour briefing to journalists, he revealed another motivation behind the plan to organize auto design and production with increased quality control.

We “never” want to see Toyota president Akio Toyoda appear before U.S. Congress again, he said through an interpreter, referring to the executive’s interrogation by lawmakers after the recall crisis. Toyoda was called to account for his company’s safety problems. The questioning was seen by many as a humiliation for the auto maker’s president.

Like most successful Japanese companies, Toyota wants to be known for its achievements. The idea of standing out in any other way is not part of the program.

Comments