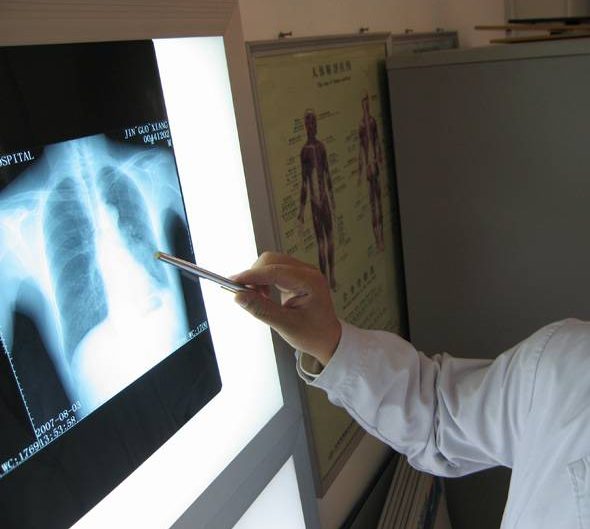

TORONTO – A new international study suggests orthopedic surgeons and their clinics can play a key role in identifying battered women and offering them help.

The work, led by researchers at McMaster University in Hamilton, suggests surgeons who work in fracture clinics unknowingly see several hundred such cases a year.

And a lead author says despite the fact these women have seen others in the health-care continuum before being referred to a fracture clinic, most have not been asked if their injuries were inflicted by a partner.

Dr. Mohit Bhandari says the injuries orthopedic surgeons see are serious; most require an operation and many involve months and even years of recovery time.

He says studies have shown that when intimate partner violence escalates to that level, the women are at real risk of being killed by their partners, so it’s important that orthopedic surgeons start to take a role.

Bhandari says orthopedic surgeons need to view it in the way the profession treats suspicious injuries in children.

“For us it’s now common. It’s ingrained in our education, in our processes and our teaching that children who come in with unwitnessed injuries … immediately trigger us to say: ‘What are the red flags? What should we be doing? Let’s think beyond the child’s injury,”‘ Bhandari says.

- What is a halal mortgage? How interest-free home financing works in Canada

- Capital gains changes are ‘really fair,’ Freeland says, as doctors cry foul

- Budget 2024 failed to spark ‘political reboot’ for Liberals, polling suggests

- Peel police chief met Sri Lankan officer a court says ‘participated’ in torture

“We need to be doing the same thing for women.”

The study, published Tuesday in the medical journal The Lancet, goes by the acronym PRAISE – the prevalence of abuse and intimate partner violence surgical evaluation. It gathered information from women who were treated at 12 fracture clinics in five countries: Canada, the United States, India, the Netherlands and Denmark.

Just under 3,000 women were asked to complete questionnaires designed to spot physical, emotional and sexual partner abuse. They were able to fill in the questionnaires in private and anonymously, which the researchers believe adds to the likelihood they would answer honestly. It’s well known that in studies some people shy away from revealing information that they find embarrassing or painful.

About 85 per cent of the women – 2,344 – agreed to take part in the study, which showed that one in six had experienced a history of intimate partner violence in the previous 12 months and one in three had experienced it at some point in their lifetime.

Bhandari lays out the study’s stark math this way:

“The average orthopedic surgeon across Canada who runs a fracture clinic will typically see somewhere between 800 to 1,000 women … across the course of their year,” he says.

“Our estimates would suggest that 300-plus of these women would come in with a lifetime history of abuse. … Two hundred of those women would come in having physical abuse at some point in their life and 20 of those women would be there … with a major fracture or dislocation requiring a procedure as a result of intentional injury from an intimate partner.”

A commentary published with the study says that while there is insufficient evidence to recommend that all health-care settings screen women for domestic violence, these findings suggest fracture clinics are a worthwhile place to look for these cases.

“Overall, the PRAISE investigators’ important and comprehensive study should help orthopedic clinicians to realize that they should suspect and ask about intimate partner violence if clinical indicators are present,” writes Kelsey Hegarty of the General Practice and Primary Health Care Academic Centre in Carlton, Australia.

Bhandari says orthopedic surgeons have traditionally underestimated the percentage of their female patients who are victims of domestic abuse, believing these events are rare. As well, he says, his colleagues have often argued that other parts of the health-care system are likely identifying and helping women find a way out of their abusive situations.

“My role is to treat the fracture. I’ve trained for years to do that. I will do that and I will ensure I can get this patient, this woman back to function,” he says, describing the mindset.

He acknowledges identifying women who are being abused isn’t enough – orthopedic surgeons need training on what to do with the information and how to help these women gain access to the support they need. He says his team is working with the Public Health Agency of Canada to develop a tool kit for orthopedic surgeons.

“We have a second chance,” he says of the role he and others in his specialty can play.

“And our chance is a critical chance because when it gets to the point (where there has been) an escalation of injury to the extent that we see, really, there is a real risk for homicide and death. And our job is to do whatever we can, obviously, to protect their safety.”

Comments