On Thursday, British voters will answer a question that seems simple: Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?

The result remains too close to call, though bookies are now predicting that Britain will stay in the EU.

So what happens on Friday morning?

A Yes vote to Brexit would raise issues that would take years to resolve, affecting everything from Scotland’s place in the United Kingdom to Canada’s free trade deal with the EU, which has not yet been approved on the European end.

READ MORE: Five questions about this week’s Brexit referendum

In the short run, however, British legislators would face the task of turning their relationship with the EU into something more like a free trade agreement.

Will Europe be willing to sign a deal? There are good reasons why they might not. Britain is not the only country in the EU where there is serious pressure to leave, and the EU may want to be seen to punish Britain for leaving, if only to show other countries that leaving wouldn’t be easy.

But ultimately self-interest would force some kind of trade deal, Conservative MP and Brexit supporter Chris Grayling told Global’s Tom Clark on The West Block on Sunday.

“In what world does any country, does any government, start a trade war with its biggest export market?” he asked.

“There are five million EU jobs that depend on British consumers. It makes no sense for them not to want to keep trading as normal. They suffer financially if they don’t carry on trading as normal.”

The issues would take years to sort out.

- Could London keep its status as an international financial centre? Possibly not. London-based banks are treated as European, allowing them to operate throughout the EU. Citizens of other EU countries can work freely in London in the financial industry. If those things change, another city – Paris, for example – may try to position itself as a banking hub, with all the jobs and money that go with that.

- A drop in the value of the pound, a widely predicted consequence of Brexit, would have winners and losers. A low pound may have advantages for manufacturers, though companies — some Canadian — which have operations in the UK (in part because it was in the EU) may have to make other plans. There’s a plausible scenario in which London suffers as financial-sector jobs leave, while industrial areas in the Midlands revive with a lower pound.

- How would a second referendum on Scottish independence play out, if nationalists are able to frame the choice as union with England or union with Europe? Scots are much more pro-EU than English voters, and independence only lost by about 10 per cent in 2014. If the first year or two of Brexit is a rough ride (and Scots vote heavily to stay in Europe Thursday, but are overruled by England), nationalists may be able to frame separation from the UK and reunion with the EU as a cautious, rational choice.

A No vote to Brexit would be less dramatic, but would reshape the EU.

However Britain votes on Thursday, the EU’s credibility, already shaken by the euro crisis that began in 2009, will be further damaged by the spectacle of a major member country deciding to stay by only a few percentage points.

But the euro crisis and the Brexit referendum crisis pull the EU in two opposite directions.

What was the euro crisis, and why does it matter?

The euro crisis, which started to unfold in 2009 and has not really been resolved, hinged on the problems caused when countries that had adopted the euro started to run up unmanageable levels of debt. That created problems for all the euro-zone countries, since individual countries’ debt was guaranteed by all of them collectively.

Greece was the worst case, but Portugal and Spain also had serious issues. More solvent countries that had adopted the euro, like Germany, were in effect forced to bail out indebted countries. This ended up causing rage on all sides, first from the countries that were doing the bailing out, then from the countries that were bailed out, as punishing austerity policies took effect.

Britain never adopted the euro, and as a result was insulated from the worst effects of the crisis, which many argued happened in the first place because potential problems of this kind were ignored when the eurozone was designed.

In Britain, the mess harmed the EU’s credibility and it made the decision to keep the pound, Britain’s most obvious point of difference with the rest of the EU, look far-sighted.

From one point of view, though, the problem that led to the euro crisis was that member countries were left too much independence — they got the benefits of easy credit, while pooling the risk, until the system collapsed.

For Grayling, the solution is unavoidable.

“I don’t believe you can have a single currency without a single government structure,” he says. “They have to move down that road, to political union, but that leaves the United Kingdom stuck on the fringes.”

VIDEO: British cabinet minister and house leader Chris Grayling who has been campaigning for Vote Leave tells Tom Clark why Brexit is the right path for Britain.

On the other hand, it is a pull toward centralizing authority in Brussels that led may Britons to want to leave the EU in the first place.

Creeping centralization

The European Union, which started as a free-trade agreement, is a state, sort of. (The euro crisis showed that it can at times have some of the responsibilities of a state without the full powers, with chaotic results.)

It has also, at times, been an international organization and a free-trade agreement.

- Iran fires air defences at military base after suspected Israeli drone attack

- Carbon rebate labelling in bank deposits fuelling confusion, minister says

- Conservatives ask interference inquiry judge to rule elections were flawed

- Senator references ‘Trumpian denialism’ in foreign interference debate around China

One school of thought argues that Europe needs a stronger central state — a “United States of Europe”. (Oddly, the term seems to have been coined by no less an icon of British bulldog defiance than Winston Churchill himself.)

The EU’s flag has always had a strong relationship to the American flag.

European treaties going back to the 1950s have committed member states to “an ever-closer union,” an ideal or threat, depending on your politics.

For Britain, which to this day has no real consensus about whether it’s part of Europe in the first place (only 15 per cent of Britons identify as European) the phrase has seemed more than a little alarming. In February during an EU summit in Brussels, Britain’s Conservative prime minister, David Cameron, succeeded in exempting Britain from the language, which had become a flashpoint in Britain’s debate about its relationship with the EU.

In a 2012 survey, only 27 per cent of respondents in the UK said they felt attached to the EU, the lowest rate in the Union, contrasting with 52 per cent in Germany and 55 per cent in France.

With its credibility bruised, there doesn’t seem to be an alternative to a two-track EU, where some countries relate to it more as a central government that sets fiscal policy, and others as more of an international organization with a trade agreement attached.

How did Britain get to this point?

Cameron promised a referendum on Britain’s relationship with the EU in January, 2013. At the time, he was about two years out from a general election in which he would have to face a new factor, the UK Independence Party.

UKIP sat on the sidelines of British politics for years as a fringe party, but by 2013 it was starting to become a more mainstream force, doing well in local elections, and, in 2014, European Parliament elections.

Cameron had the most to lose from a strengthening UKIP — the party draws its support in large part from ex-Conservative voters — and he needed a bone to throw them.

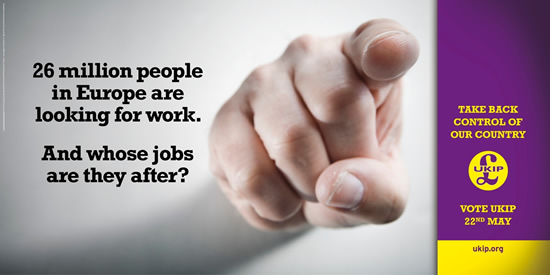

UKIP is a social conservative party which favours increased defence spending, but its main issues, which it sees as linked, are controlling and restricting immigration and leaving the EU.

“There are 550 million people who have the right to come and settle in the United Kingdom, and every year more and more are coming,” Grayling says.

Here is one of their ads:

“While the middle classes have benefited from the skills these newcomers have brought, their presence has increased feelings of insecurity among the working class, who see the world changing at an ever greater pace and worry about their children’s future,” singer-songwriter Billy Bragg wrote Monday in the Guardian. “At the mercy of the invisible forces of globalisation, when someone offers them the chance to “take back control,” they’re likely to respond in the affirmative.”

Last week, UKIP leader Nigel Farage attracted angry controversy when he unveiled a billboard showing a crowd of refugees in the Balkans in 2015 reading “Breaking point: the EU has failed us all. We must break free of the EU and take control of our borders.”

VIDEO: UK Independence Party (UKIP) leader Nigel Farage has defended a controversial poster released by his party in the run-up to the country’s referendum on EU membership. Farage said the timing of the release of his campaign poster, 90 minutes before the murder of MP Jo Cox, had been “deeply unfortunate”.

Almost immediately afterward, Labour MP Jo Cox, a mother of two young children, was murdered near her constituency office by a man associated with the far-right nationalist group Britain First. Britain First has a place on the same spectrum as UKIP, but is more extreme.

(Thomas Mair, the accused in Cox’s killing, shouted “Death to traitors! Freedom for Britain!” when asked his name during a court appearance Saturday.)

Many wondered if there was an indirect but real connection between Farage’s abrasive rhetoric, in the emotional leadup to Thursday’s vote, and Cox’s murder. Both sides suspended their campaigns.

In the aftermath of Cox’s death, Scottish National Party leader Nicola Sturgeon said that the Brexit debate had become ” really, really distasteful … a little bit poisonous and a little bit intolerant and focused on fear of foreigners as opposed to legitimate debate about immigration.”

For good or ill, Britain and the EU won’t be the same on Friday morning.

VIDEO: Sat, Jun 18: The suspect in Thursday’s shooting and stabbing of British MP Jo Cox identified himself as “Death to traitors, freedom for Britain” during his first court appearance today. Jacques Bourbeau has the latest.

Comments