Ever wonder why some members of your family seem immune to a stomach bug that leaves others out of commission for days?

It turns out people’s resistance to certain germs may come down to their DNA, according to a study published in this month’s Journal of Infectious Diseases.

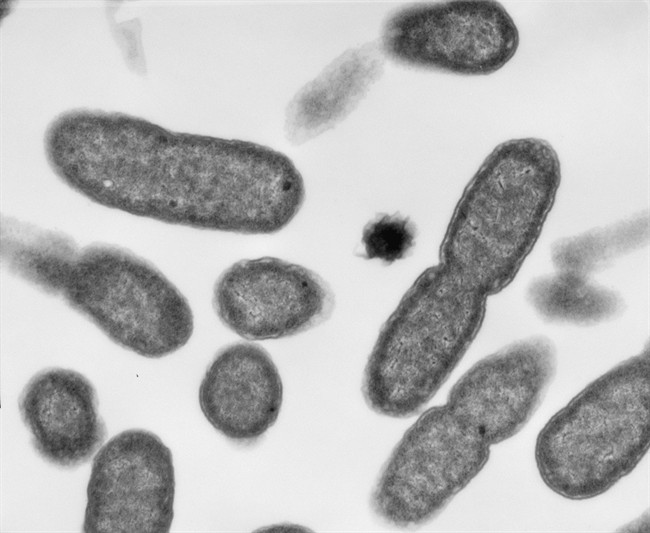

For their experiment, researchers at Duke University made 30 healthy adults drink an E. coli-tainted slurry. Six of the participants came down with severe stomach symptoms, while six showed no symptoms at all.

The blood of both groups was then examined in the hopes of figuring out what differentiated them. The conclusion? There may be genetic traits that can increase or decrease a person’s chances of being infected after exposure to a bacteria.

READ MORE: Common wisdom about the common cold – what should you believe?

“The discovery of those genes for this particular biology is new. They had not previously been implicated in the resilience to infection.”

Dietrich Stephan, a professor and chairman of the department of human genetics at the University of Pittsburgh, told NBC’s Today that he finds the study “intriguing” and that he’d like to see the findings replicated with more participants.

- Health task force blasted over ‘dangerous guidance’ for cancer screenings

- Dentists hesitant to sign up for federal dental plan; seniors advised to look at all options

- David Chang’s Momofuku to stop ‘chile crunch’ trademark battle after outcry

- Over 25% of young Canadian deaths linked to opioids amid pandemic: study

Tsalik agrees and says while more research needs to be done, this discovery is a promising first step. He believes further investigations could help create better treatments or even help identify how to stop infections before they start.

READ MORE: Genome test may be key in diagnosing mysterious rare disorders in children

Treatment could prove particularly valuable in an outbreak situation.

“If you can find something that is less disruptive to a person’s biology than taking antibiotics — and you can provide some element of protection as they’re about to go into an known high-risk environment — that could be a great application for these sorts of findings.”

Comments