EDMONTON — Few parents would choose to take the walk Kelly Slifka takes, let alone as often as she does.

For the past month, Slifka has regularly visited the base of the High Level Bridge.

There’s a paved path that takes her to a spot between two of the towering supports, then a well-worn gravel track beneath the hulking bridge.

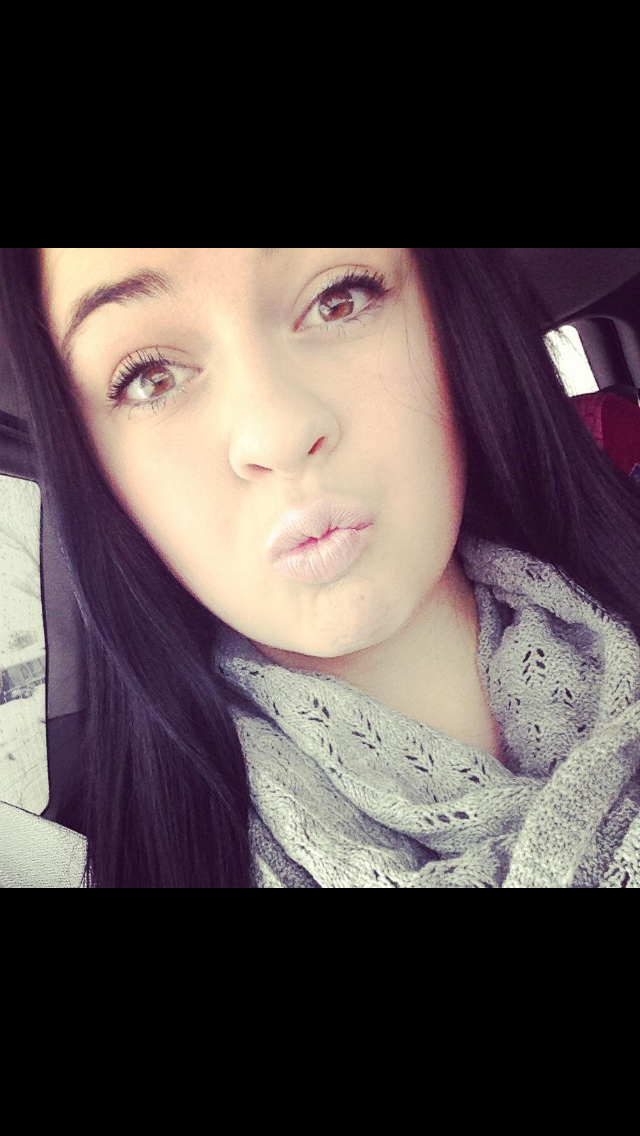

She stops next to a massive concrete footing where pictures of her daughter sit on the wet grass beside a bundle of white roses, one for each of Kylee Goodine’s 17 years.

“Because Kylee chose to take her life at this spot,” says Slifka, “it’s important for me to come here to acknowledge that.”

Slifka’s walks have another purpose. She says Alberta’s mental health care system failed her daughter and she’s demanding improvements.

Alberta’s suicide rate is the third-highest in the country. Every year, about 500 die by suicide. In comparison, 369 Albertans died last year in vehicle collisions.

“Our mental health care system is over-stressed and over-burdened,” says Jodie Mandick, who’s with The Support Network. “There are not enough beds.”

It’s not a new problem. In 2008, Alberta’s auditor general urged the province to develop a better, coordinated mental health treatment plan.

In 2011, the province introduced an addiction and mental health strategy but did little to implement it.

Then last July, the auditor general once again reviewed mental health treatment and again urged the province to act.

Mandick and other mental health professionals are used to the delays. She was not surprised to hear Kylee’s story.

“It seems particularly tragic because there were all of these markers in place to let us know that this person was really in need of some help.”

On Sept. 27, Kylee’s best friend called police after Kylee said goodbye and started to give away her things. When police arrived, Kylee said she was fine. The officers left, telling her a mental health worker would soon call to check up on her.

Two days later, Kylee said the same things to a different friend. Police visited and again, Kylee said she was fine and they left.

On Oct. 2, Kylee was in Old Strathcona with a friend, left the car to use the washroom and did not return.

She did contact her mom.

“She had texted me her goodbyes, telling me that she was going to end her life and there was nothing I could do to stop her.”

Slifka called the friend, who raced to the bridge. By then, police had arrived and three bystanders were holding Kylee back.

Police took Kylee to the University Hospital. Slifka raced there, too, and the staff told her they had spoken with Kylee and she seemed OK.

“I just said, ‘She’s lying to you. There’s no healthy person who comes to a bridge.’ I mentioned the Mental Health Act. There’s a 72-hour hold.”

In certain cases, Alberta’s act permits holding patients against their will for 72 hours.

But the hospital told her there were no beds available, Slifka says, and offered her some help-line numbers and pamphlets.

Kylee went back to the bridge the next day.

“The next message I got, she said goodbye and I love you,” Slifka says. “I said, ‘Kylee, please.’

“Then she said goodbye. I love you. I’m at the bridge. Then her phone went dead.”

Two days later, a mental health worker called Slifka to ask how Kylee was doing. Too late.

WATCH: Seventeen-year-old Kylee Goodine took her own life last month and her mother says it didn’t have to happen. She’s demanding better mental health care. Fletcher Kent has more on the problems and how lawmakers are working to change things.

Alberta’s health minister promises action soon.

“We know that the government needs to do more on supporting mental health and addictions,” says Sarah Hoffman. “This is an area of growing pressure.”

In June, the new NDP government created the Mental Health Review Committee. Hoffman says she expects a report by the end of this year and she wants to act on its recommendations immediately, using the $10 million in extra mental health care funding in last month’s provincial budget.

“We want to make sure there is some money to move quickly on some of the initiatives that are being brought forward through the review.”

The remaining recommendations will be addressed in the next budget, expected in March. But the province’s efforts won’t just be about money, Hoffman adds. She expects the committee will call for better collaboration between governments, police and support agencies.

She says her goal is to give people hope.

That’s what Slifka wants, too, with her walks and her makeshift memorial.

“I hope that when people walk by, people have that thought of what’s happened here.”

Comments