WATCH ABOVE: While taking opioid drugs can lead to sometimes deadly consequences, it seems doctors are prescribing them more and more. Global’s Erika Tucker takes a look at the usage of the painkillers in Alberta.

David Juurlink sees them daily — old and young, with strokes or pneumonia or broken bones or drug-related overdoses, accidents, constipation.

Their ailments and backgrounds and health conditions run the gamut. And they’re all on high doses of a drug five times more powerful than morphine.

“It’s extremely common to admit people to hospital on the most potent oral opioid available,” said Juurlink, an internist and head of Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

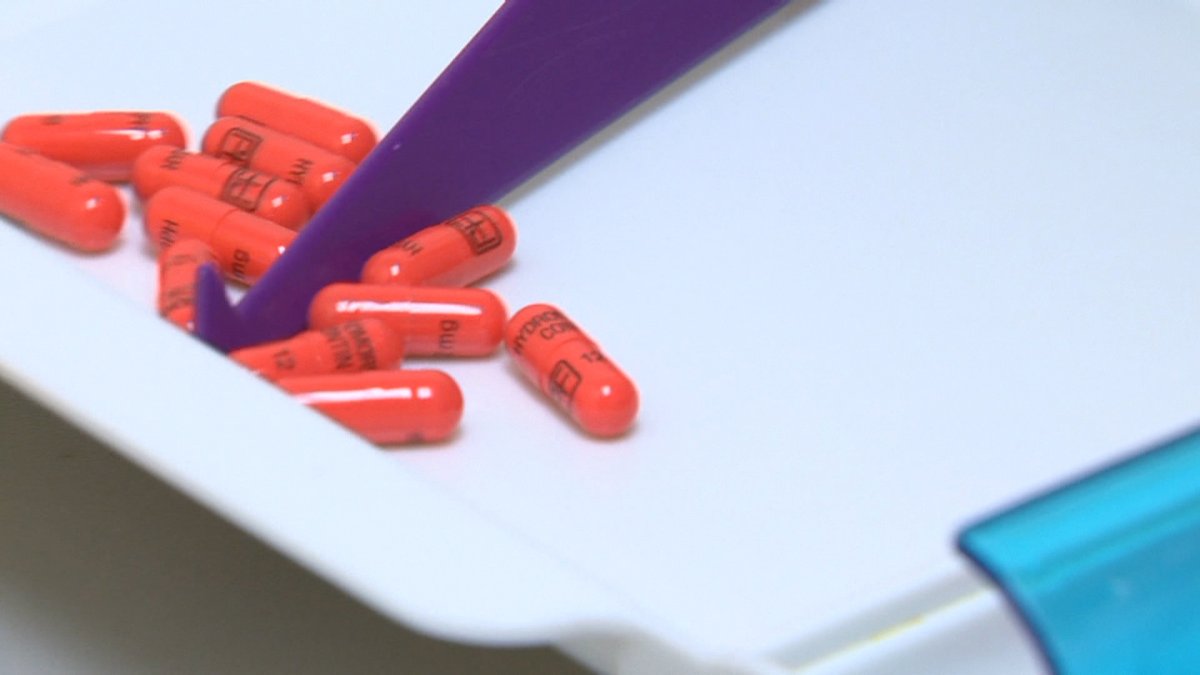

Prescriptions for Hydromorph Contin in Ontario have more than doubled in three years, even as other drugs have dropped or plateaued.

In June, more than 76,000 prescriptions were filled in the province — the vast majority of those covered by the Ontario Drug Benefit.

- Freeland set to table 2024 federal budget in the House of Commons

- All a-boot tradition: A look at finance ministers’ budget shoes through the years

- Inflation ticked higher in March. Are Bank of Canada rate cuts still in the cards?

- Food service strike: Air Canada, WestJet refine menus at Toronto Pearson

And in Alberta, where OxyNEO and generic oxycodone are more readily available, opioid prescriptions have almost doubled and Hydromorph Contin prescriptions have tripled since 2009:

The number of Albertans being prescribed Hydromorph Contin has almost quadrupled in that time:

Years after OxyContin was discontinued and replaced by a “tamper-resistant” formulation, Canadians are popping more addictive, potentially deadly painkillers than ever.

“Doctors simply started writing prescriptions for the drug that was covered, which was Hydromorph Contin,” Juurlink said.

Purdue Pharmaceuticals, the company that made OxyContin and makes OxyNEO and Hydromorph Contin, said in an e-mail Monday it’s “actively working” to make Hydromorph Contin and the rest of its opioid painkillers “tamper-resistant” but wouldn’t say when that will happen.

“We are unable to comment on the timeframe for converting Hydromorph Contin or its abuse deterrent technology platform as both are proprietary confidential information until approved by Health Canada,” spokesperson Lucy Lai wrote.

Canada’s doctor-driven epidemic

Doctor Mel Kahan calls it an “iatrogenic” epidemic — a disease caused by some doctors.

That makes it much trickier to tackle: The drugs are legal, usually legitimately obtained and more often than not for legitimate reasons: People in pain need treatment. The vast majority of doctors writing these prescriptions do so in good faith, because they want to help their patients.

Global News has reported on the rise of drugs replacing OxyContin — and their deadly consequences — multiple times over the past two years.

IN DEPTH: Canada’s pill problem

Six hundred Ontarians a year are killed by opioid toxicity; same goes for close to 140 Albertans, according to the province’s coroner (and that’s just the ones we know for sure: Many more are suspected but not confirmed to have an opioid causal link).

But we don’t have a good national picture of prescription opioids’ toll because no one’s collecting that data nationally — Health Canada has said that’s up to the provinces.

And neither provincial governments, the federal government nor provincial Colleges of Physicians seem inclined to take additional steps to crack down on Canada’s pill problem.

Health Minister Rona Ambrose established a $3.6-million fund for projects promoting safer prescribing, and has said she wants to make all oxycodone, the active ingredient in OxyContin and OxyNEO, tamper-resistant.

READ MORE: Health Canada looks for ways to make opioid prescribing safer

But that won’t change the status quo for Hydromorph Contin and Fentanyl, two powerful opioids that have become heavily prescribed and increasingly prone to abuse.

A string of Fentanyl deaths in multiple Canadian provinces has sparked warnings from law enforcement of the dangers of the drug, which is much more potent than many realize.

READ MORE: Police ramp up efforts following Fentanyl deaths

Easy to get hooked, tough to get treatment

More often than not, when people who find themselves addicted try to get help, there’s none available.

Alberta has the treatment facilities for about one tenth of the people who need it, says Hakique Virani, an addiction medicine and public health specialist in Edmonton.

“There’s absolutely not enough treatment available,” he said.

Addicts overwhelmingly seek treatment, Virani said, “if it’s seen to be readily accessible.”

“If it’s not, the phone calls stop.” And people spiral further into addiction, dysfunction and, frequently, crime.

“We treat everything like a moral issue and not like a medical issue.”

READ MORE: Recreational drug use turns deadly in Saskatchewan

Too often, he said, addiction is treated as a moral rather than medical failing. So the medically proven treatment, such as methadone and suboxone, isn’t available.

The irony of an addiction driven by over-prescribing and worsened by under-prescribing doesn’t escape Virani.

“When it comes to chronic pain, we’re really eager to treat it with drugs that we know don’t work,” he said.

“It’s just weird to me how on one side, where there’s no evidence, we want to treat with medication. And on the other side, where there is evidence, we don’t want to treat with medication.

“We stigmatize addiction disorders as anything but a medical condition.”

READ MORE: Fake OxyContin warning sounded after 2 deaths in Saskatchewan

How do you curb problematic prescribing?

Juurlink wants to see stricter prescribing practices — requiring any physician writing scrips for more than 200mg of morphine equivalent a day (about 40mg of Hydromorph Contin) to have special pain treatment training.

“And a lot of doctors who are prescribing high-dose opioids don’t know what they’re doing. …

“Doctors don’t like hearing that message. But they have to hear it, because people are dying because of what we’re doing.”

Easier said than done: There’s no specialized opioid-prescribing training program in place.

“It’s a difficult suggestion to operationalize,” Juurlink admitted. “But the alternative is the status quo.”

READ MORE: Vancouver couple accused of being Fentanyl ‘kingpins’

Another possibility is stricter federal regulation. But that’s tricky given that Health Canada has already approved these drugs.

It doesn’t appear anyone’s willing to step up to that regulatory plate, however.

READ MORE: Fentanyl use on the rise in Nova Scotia

Ontario Health Minister Eric Hoskins has said in the past he doesn’t see a need for a further crackdown on opioid prescribing, despite opposition calls for the government to act.

Ontario’s College of Physicians and Surgeons referred questions on whether it would impose stricter painkiller prescribing rules to McMaster University’s Michael G. DeGroote National Pain Centre, which did not immediately return a request for comment.

“The College does have a Prescribing Drugs Policy that all doctors are expected to follow,” said Prithi Yelaja.

“Moreover, if the College receives a complaint about an individual doctor’s practice of prescribing drugs, including opioids, we will investigate.”

In its section addressing drug misuse and abuse, that policy notes it “does not attempt to curb the prescribing of narcotics and controlled substances for legitimate reasons … but does reinforce the requirement that physicians prescribe these drugs in an appropriate manner.”

But Juurlink said these guidelines demonstrably good enough.

“If doctors don’t willingly reduce their prescribing of opioids — and they have to, or people are going to continue to die — then there has to be some forcing function.

“And if that won’t come from a provincial regulator, and it won’t come from a national regulator, what’s the alternative?”

Changing prescribing practices without making it easier to seek treatment only solves half the problem, Virani said.

“If you leave opiate use disorder untreated, it’s like leaving someone hungry: They’re going to find food somehow,” he said.

“You leave them without treatment, they’ll find another way.”

Have you or a loved one struggled with prescription opioid abuse, misuse, addiction? We want to hear from you.

Note: While we may use your story in this or other articles, and give you a shout if we have questions, we won’t share or publish your contact information.

Comments