COLUMBIA, S.C. – More than 70 years after the state of South Carolina sent a 14-year-old black boy to the electric chair after the killings of two white girls in a segregated mill town, a judge threw out his conviction, saying the state committed a great injustice.

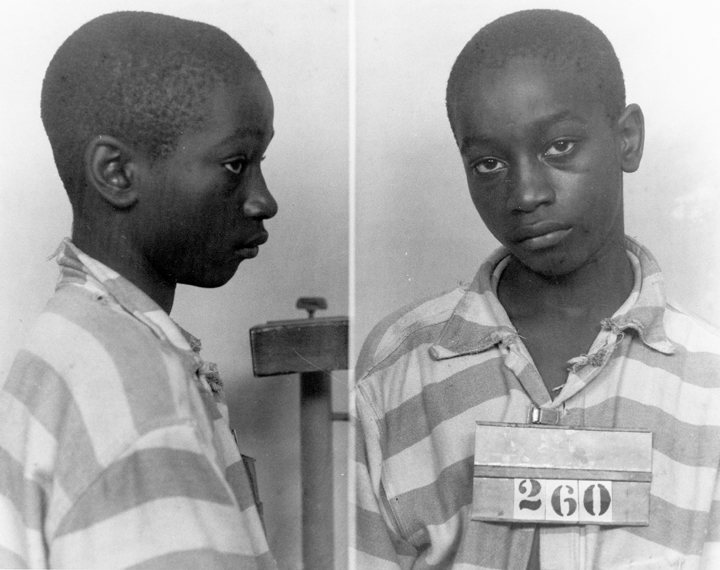

George Stinney was arrested, convicted of murder in a one-day trial and executed in 1944 – all in the span of about three months and without an appeal. The speed in which South Carolina meted out justice against the youngest person executed in the United States in the 20th century was shocking and extremely unfair, Circuit Judge Carmen Mullen wrote in her ruling Wednesday.

“I can think of no greater injustice,” Mullen wrote.

Stinney’s case has long been spoken of by civil rights activists as an example of how a black person could be wronged by a southern justice system that sanctioned legal discrimination, when the investigators, prosecutors and juries were all white.

READ MORE: Alabama pardons ‘Scottsboro Boys’ in 1931 rape case

The two girls, ages 7 and 11, had been beaten badly in the head. A search by dozens of people found their bodies. Investigators arrested Stinney, saying witnesses saw him with the girls as they picked flowers. He was kept him from his parents, and authorities later said he confessed.

His supporters said he was a small, frail boy so scared that he said whatever he thought would make the authorities happy. They said there was no physical evidence linking him to the death. His executioners noted the electric chair straps didn’t fit him, and an electrode was too big for his leg.

In January, Mullen heard testimony during a two-day hearing. Most of the evidence from the original trial was gone and almost all the witnesses were dead.

It took Mullen nearly four times as long to issue her ruling as it took in 1944 to go from Stinney’s arrest to execution.

Her 29-page order included references to the 1931 Scottsboro Boys case in Alabama, where nine black teens were convicted of raping two white women. Eight of them were sentenced to death.

The convictions were eventually overturned before the teens went to the death chamber and the charges were dropped. Mullen noted Stinney did not even get the consideration of an appeal.

The judge was careful to say her ruling doesn’t apply to other families who felt their relatives were discriminated against.

Comments