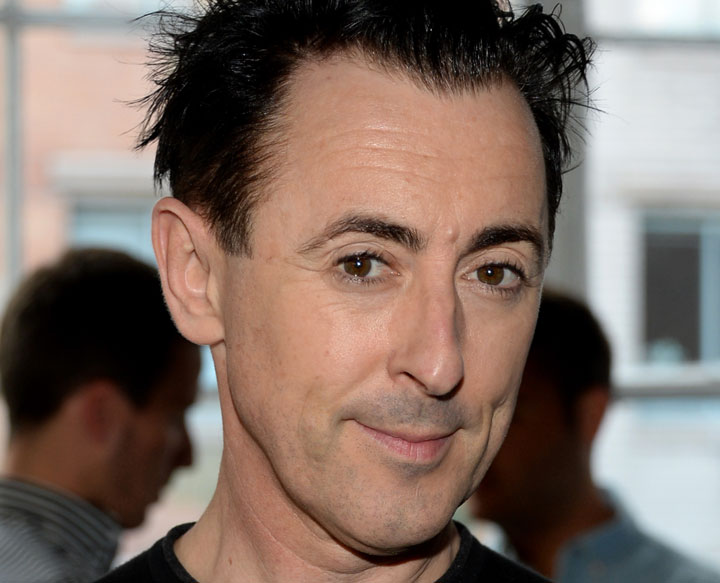

TORONTO – When Scottish actor Alan Cumming was 28, he endured an episode he’s come to believe was a nervous breakdown — or, as he memorably refers to it in his new memoir, a “Nervy B.”

He was eight years into a marriage to actress Hilary Lyon and the couple was trying to have a child. As parenthood loomed and Cumming became increasingly swallowed by anxiety, he started to realize he hadn’t quite escaped the dark shadow of his own father.

As documented in Not My Father’s Son, the Tony Award-winning actor was raised by a mercurial terror who subjected Cumming and his brother, Tom, to a routine of jarring physical violence and withering verbal criticism.

Then 28 years old and considering the reality of fatherhood for the first time, Cumming worried about a cycle of violence. Now 49 and still childless, Cumming says he remains vigilant for echoes of his deceased dad.

“I’m not a father, and I’ve chosen not to be now,” he said during an interview in Toronto this week. “Sometimes if I get annoyed with a child, or even my dogs, I sort of think: ‘Oh gosh.’ I sometimes check myself.

“That will never go away — that worry,” he added. “Because I am my father’s (son). I have madness on both sides of my family. Let’s face it. It’s a miracle I’m functioning.”

He laughs, in rapid triplets, then continues.

“I’m being trite but it’s true. I do think it’s something that I will go through my life always being conscious of.”

READ MORE: Actor Alan Cumming speaks out against infant circumcision

Although Cumming just worked the book’s title into conversation casually, it’s actually quite a loaded statement for the multi-hyphenate star — one that launched a “crazy summer” that served as the setting for Cumming’s memoir.

It was 2010, and Cumming was participating in the British genealogy documentary Who Do You Think You Are? As he was preparing to climb his family tree, he fell into contact with his father for the first time in more than a decade.

His dad was dying of cancer and had troubling news for his family: Alan Cumming, he was certain, was not actually his son but instead the product of an extramarital affair pursued by Cumming’s beloved mother.

Just as he was reeling from this revelation, Cumming was reaching profound conclusions in his documentary-aided investigation into the mysterious death of his maternal grandfather, a British soldier named Tommy Darling who had disappeared into a life in Malaysia marked in equal measure by honour and havoc.

Cumming documents the dual familial probes in sometimes alternating chapters in his tightly focused memoir. And he does eventually find out whether his own father was telling the truth — but it would spoil the book’s suspenseful build to reveal that answer here.

For a long time, the typically forthcoming actor was uncharacteristically terse on the topic of his father. In the U.K., where Cumming’s life has long been a subject of interest to the tabloid press, it had been established that Cumming and his father were estranged but the reasons why were somewhat blurry.

Even those closest to Cumming were stunned to read his account of a childhood spent weathering a campaign of psychological cruelty and intimidation.

“My friends are shocked,” said Cumming, nattily clad in a royal blue dress shirt and black vest.

Growing up on a picturesque Scottish estate, Cumming lived under the constant threat of violence or degradation.

In one of many chilling memories, he writes about his father flying into a rage over Cumming’s supposedly shaggy hair. His dad dragged him by the scruff of his neck for dozens of yards, threw him across a workbench and shaved his head roughly with a pair of rusty clippers he usually used to shear sheep.

These recollections mostly stayed buried until the aforementioned “Nervy B,” at which point Cumming started dealing with his past.

“I realized that for a few years prior to that, I’d have episodes where I got really upset and irrational and I couldn’t understand why. I’d just put it down to being overtired or working too much,” said Cumming, who still speaks with a prominent Scottish accent.

“Over a long period of time, it wasn’t going away. It just wasn’t. This depression and inability to function properly wasn’t going away.”

READ MORE: Latest LGBT news

That was more than two decades ago, and of course much has happened in his life since then. He won his Tony in 1998 for a starring run in Cabaret, and has pursued an unusually eclectic career onscreen with notable roles in the disparate likes of X-Men 2, GoldenEye, Eyes Wide Shut, the Spy Kids franchise, Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion, Circle of Friends, and, recently, The Good Wife, as resourceful and excitable campaign manager Eli Gold.

He’s put his name to a photography exhibition, a fragrance, a one-man show, an album based on that one-man show and a novel.

With Cumming’s recent disclosure of childhood abuse, some write-ups have mused on a possible link between his punitive upbringing and his relentless professional output. That implication makes Cumming uneasy.

“There’s lots of people who have gone through terrible things,” he pointed out. “I don’t think my success is connected. I think perhaps my work ethic — I’m used to working a lot.

“But lots of people work hard,” he added with a wry smile, “and aren’t necessarily top international celebrities.”

Still, Cumming’s multi-disciplinary gamesmanship certainly indicates a confidence that seems to have sprouted in defiance of his father’s ritual humiliation.

He credits his loving mother — whom he always calls by her full name, Mary Darling — with balancing his father’s sneering disapproval.

“My dad told me I was worthless repeatedly and my mom told me I was precious, and I just — I really did at an early age not believe either of them,” Cumming said.

“I made up my own mind. I think I’m very objective about where I am in the world and how I’m perceived and aware of my own power. I’ve done that since I was a child. When I was powerless, I knew that and had to work ways to deal with it.

“I think my confidence is because it’s all gone pretty well. Heh heh. And also because it’s always been on my terms.”

Considerations of parenthood lingered for Cumming, by the way, beyond that anxious time in his 20s.

In 2002, Cumming published the novel Tommy’s Tale — a “thinly veiled memoir” that he now realizes was “very much about me wanting to become a father.” As recently as 2006, Cumming mused to a reporter that he might like to adopt.

Now, however — months away from his 50th birthday and years into his marriage to longtime partner Grant Shaffer — Cumming has confidently closed the book on fatherhood.

“I did want to do that, and I really don’t now,” he said. “I think I got older and I got content. And I don’t want to change that. I’m content. So I don’t think a child is something that I need to fulfil me anymore.”

Comments