BERLIN – How do you land a spacecraft on a comet that is streaking by at 41,000 mph (66,000 kph)?

That’s a problem scientists have been grappling with for more than a decade as they prepare for one of the most audacious space adventures ever – the European Space Agency’s attempt to land a scientific probe on the giant ball of ice and dust known as 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

They’ll find out Wednesday whether their plan will work when the agency’s mission control centre in Darmstadt, Germany, gives its unmanned Rosetta space probe the final go-ahead to drop a lander on the comet.

The event marks the climax of Rosetta’s decade-long journey to study the icy celestial bodies that have long fascinated humanity. Scientists hope that the data collected by Rosetta and its sidekick lander, Philae, will provide insights into the origins of comets and other objects in the universe.

On Tuesday, the agency announced that systems aboard the Philae lander had failed to switch on properly at first. Fearing a cosmic calamity, scientists tried a reboot.

“The lander successfully powered up, and preparations are now continuing as planned,” the agency said on its website.

The hitch demonstrates how much can still go wrong with the 1.3 billion euro ($1.62 billion) mission first conceived more than two decades ago.

Launched in 2004 after a year’s delay, the Rosetta spacecraft had to swing around Earth three times – and once around Mars – to gain enough speed to chase down the comet. After travelling 6.4 billion kilometres (4 billion miles), it pulled up alongside 67P in August.

Now Rosetta and the comet are flying in tandem at 41,000 mph between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, 500 million kilometres (311 million miles) from Earth. The vast distance means the European Space Agency has to rely on NASA’s Deep Space Network of giant radio antennas to communicate with Rosetta.

Early Wednesday, Rosetta will execute a series of complicated manoeuvrs to reach the optimum drop-off point. About 0835 GMT (3:35 a.m. EST), the lander will separate from the mother ship.

If anything goes wrong then, scientists will be powerless to do anything but watch. Since it takes more than 28 minutes for a command to reach Rosetta, the lander has been programmed to perform the touchdown autonomously.

The landing site – dubbed Agilkia after an island on the river Nile – was chosen because it is fairly free of boulders. But even the smallest error could put Philae hundreds of meters (yards) off course during its seven-hour descent to the comet.

Once the 100-kilogram (220-pound) lander touches down, it will fire two harpoons into the 4-kilometre (2.5-mile) wide comet’s icy surface to avoid bouncing off due to the low gravity.

Experts have likened the process to flying over a city and trying to hit a specific spot with a balloon.

Confirmation of the landing is expected to reach Earth at about 1603 GMT (11:03 a.m. EST).

Even if the landing fails, mission manager Fred Jansen said Rosetta alone will be able to gather much of the data that scientists hope will help them learn more about the origins of comets, stars, planets and even life on Earth.

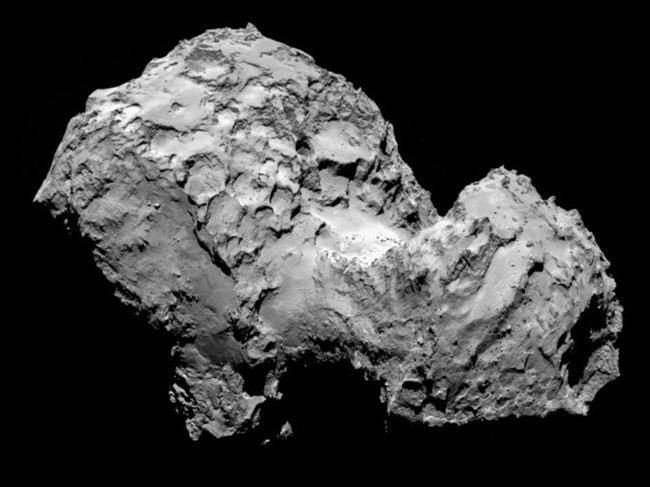

Already scientists have made a number of exciting discoveries about the comet. Close-up pictures sent back to Earth in July show it’s shaped a bit like a giant duck, suggesting that it may be the result of two comets that collided.

Last month, one of Rosetta’s 11 on-board instruments found that the comet’s coma, the fuzzy head surrounding the nucleus, is made up of chemicals that on Earth would smell like rotten eggs and vinegar, among other things.

And on Tuesday the European Space Agency said it had determined the ‘sound’ of the comet, likely caused by the release of particles into space becoming electrically charged. As the comet makes its closest approach to the sun – the point called perihelion – the amount of matter it releases will greatly increase.

“We’ll watch this comet evolve,” said project scientist Matt Taylor. “It’s never been done before.”

Comments