What’s the bare minimum you need to get by?

Across Canada, the minimum wage won’t get you there.

“You have to put off certain things to pay for others, and rotate it off. … You have to be creative, you know?”

Working full-time at minimum wage; still below the poverty line

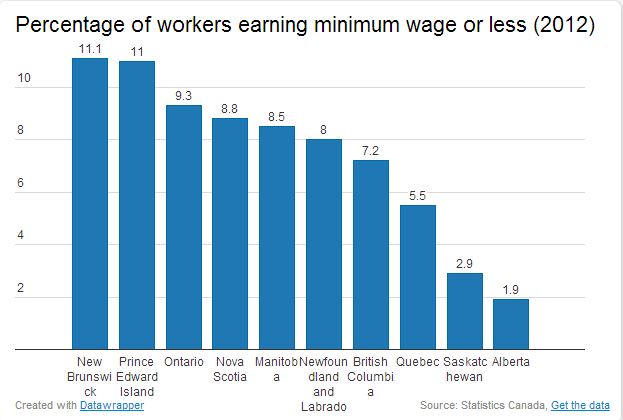

Saskatchewan and Alberta, the two provinces where the gap between the poverty line and the minimum wage is biggest, also boast the smallest percentage of their workforces making minimum wage or less.

Ontario, on the other hand, has both a sizable gap and a sizable portion of its working population – almost one person in 10 – making minimum wage or lower.

Tussles over wages are in the news on both sides of the border: U.S. President Barack Obama has made raising the minimum wage a personal priority; a narrow victory (affirmed by recount) giving SeaTac, WA the highest minimum wage in the U.S. at $15 an hour faces a court challenge this week; California workers at a Wal-Mart warehouse reached a multi-million-dollar settlement over alleged wage theft this month.

And Ontario’s preparing to debate on its own minimum wage: A slew of recommendations is due this month and should be made public in January. The province won’t comment on the kind of steps it might take as a result, but advocates are hoping for a significantly higher minimum with built-in annual increases.

“It is in the public good for us to wrestle this out of the political realm,” says Frances Lankin.

As a former economic development minister, former head of Toronto’s United Way and author of a study on how to fix the province’s social assistance network, Lankin has become intimately familiar with Ontario’s neediest.

- Roll Up To Win? Tim Hortons says $55K boat win email was ‘human error’

- Bird flu risk to humans an ‘enormous concern,’ WHO says. Here’s what to know

- Halifax homeless encampment hits double capacity, officials mull next step

- Ontario premier calls cost of gas ‘absolutely disgusting,’ raises price-gouging concerns

She argues we need a higher minimum wage for both human and economic reasons. “Those individuals are all part of the economy.”

And they’re badly needed for any kind of consumer-driven recovery.

The most common argument against a higher minimum wage is that the added cost puts a damper on employment: No one wants to hire pricier employees; some businesses can’t afford to. Lowest-skilled labourers could get “priced out” of the market.

But comparisons of adjacent counties in different states with different wage structures found changes to the minimum had no adverse effect on employment.

Hiking minimum wages at the peak of a recession can augment those job losses. But as we’re repeatedly told, we’re in the midst of a “fragile recovery” – one Yalnizyan argues could be boosted by better pay.

But what about a recent exodus of companies – Heinz, Kellogg, Cargill, Novartis – whose shuttered factories leave hundreds out of work? Would they have stuck around if they’d been allowed to pay employees less? (Rob Fairholm, an economist with the Centre for Spatial Economics, suspects it has more to do with a high loonie)

“I know there is an incredible downward pressure on salaries that’s happening globally, and certainly happening here in Canada. And there are very, very negative implications of that,” Lankin said.

“People can very cavalierly say, ‘If you raise, we will leave; if you lower, we will stay.’ And in the long run, there’s often many more fundamental issues at play.”

A historical comparison of inflation-adjusted minimum wages indicates you would’ve gotten paid far more in the 1970s than you would earning minimum wage today. Yalnizyan attributes this to a “zeitgeist” in the 1960s and ’70s in which eliminating poverty was more of a priority than it is today.

Ultimately, Lankin warns, hourly wages may not be the issue: At least as important are health benefits and pensions that provide stability a simple raise won’t. Making a couple bucks more an hour makes less of a difference if you’re out of luck when you get sick. And, in a temp-heavy labour economy, those benefits are becoming rarer.

With this in mind, from her own financial experience, Smith suggests a minimum wage of $15 an hour – equivalent to the wage being appealed in a Washington courtroom this week.

“It’s not like back in the days when you worked with a company, you’re getting benefits,” she said. “I think $15 minimum wage is good for someone who doesn’t have medical, dental – you’ve gotta pay that out of your pocket.”

READ MORE: Income mapped – how has your neighbourhood changed in a decade?

Comments